Experts involved in a unique Covid-19 study at Morriston Hospital had to go to extreme measures while recruiting patients to the cause.

They went way beyond the clichéd image of researchers as people in white coats peering down microscopes in laboratories.

Instead, two of the team from the hospital’s Welsh Centre for Emergency Medicine Research donned PPE gear to go into Covid hotspots including the emergency department and intensive care.

There they screened patients to check whether they were suitable and willing to take part, and took blood samples if they were.

They then set up a kind of human chain to ensure the blood was taken to the lab for processing without a second’s delay.

Around 1,000 patients were screened between last October and the end of January, with the target of 155 patients achieved months early.

They provided hundreds of blood samples for the Welsh Government-funded investigation – the only one of its kind in the UK – into one of the most devastating effects of the virus on the body.

Covid-19 is known to trigger the formation of abnormal blood clots that may damage organs such as the brain and lungs and could cause life-threatening complications such as stroke.

The centre is looking into why this happens, using new biomarkers the team previously developed with Swansea University to screen patients at risk of thromboembolic disease such as stroke and sepsis.

As well as gaining a better understanding of why the virus causes these abnormal clots, the study will focus on how drugs such as dexamethasone and anticoagulants like heparin affect the disease process and outcome.

The study involved screening patients with suspected Covid when they arrived in Morriston Hospital’s Emergency Department.

Blood samples were taken from those who agreed to take part, and carried straight to the centre’s laboratory just outside the main ED area.

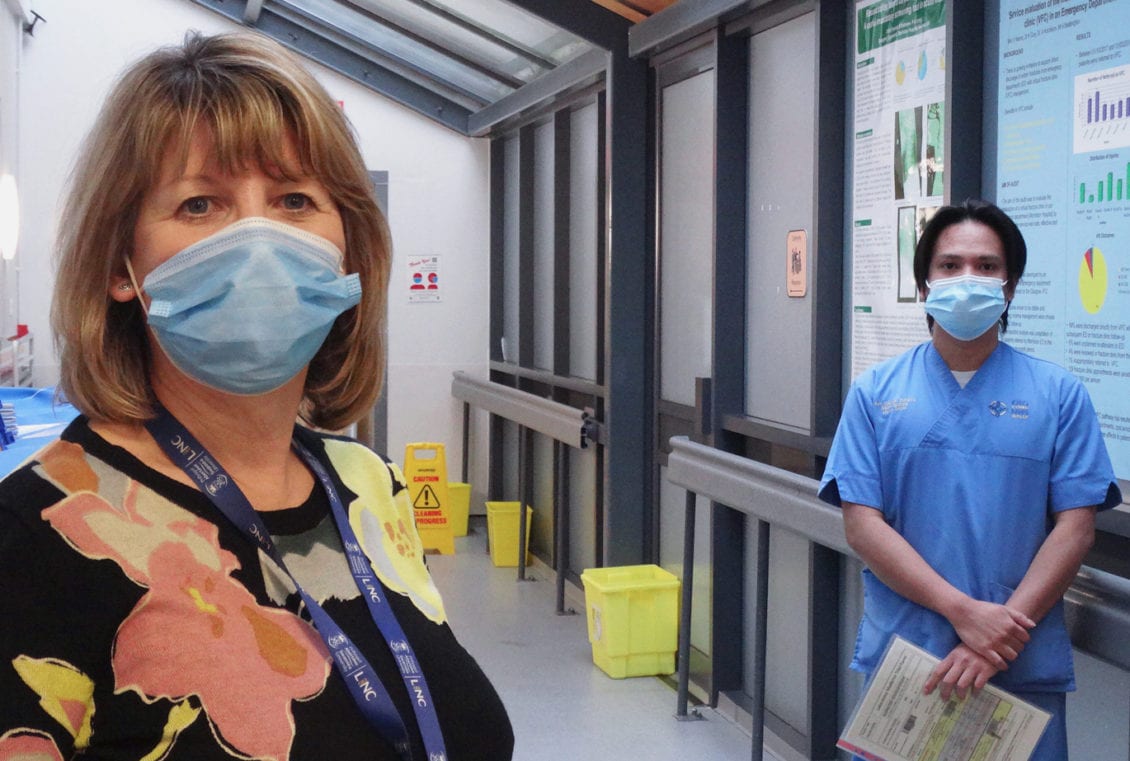

Research assistant Jan Whitley and research nurse Jun Cezar Zaldua, who joined the team on secondment last autumn specifically for this study, were at the forefront of the screening and blood sample collection.

Jun, wearing full PPE, went into the “red” areas where the Covid-suspected patients had been taken.

He explained the research study to them and, if they consented to become involved, took samples of their blood.

“I had to explain to the patients what the research was about and its importance,” said Jun.

“I really had to communicate to the patients in a very clear and concise manner. That was the most challenging part. They were struggling to breathe and they didn’t really feel well.

“Some felt so unwell that they didn’t want to take part. But most of them really wanted to help. They didn’t want others to be in that situation, because they were struggling.”

Time was of the essence as the blood samples had to be taken to the lab before they could clot. Jan waited in ED but outside the red areas for Jun to hand over the samples, which she then took to the lab.

“PPE throws up its own difficulties,” she explained.

“We always needed a team of three people, someone taking the blood and someone outside of the red area who was still protected but not in full PPE, who could leave and bring the blood samples straight back to the laboratory.”

The third person in the chain was the scientist in the laboratory who immediately loaded the samples into a rheometer, a device used to analyse the blood using the centre’s bespoke biomarker.

This would have been either Dr Matthew Lawrence or Professor Karl Hawkins, who undertook specific testing.

Not all patients who went through the initial screening could participate in the study even if they wanted to, as certain criteria had to be met.

Some who were suspected Covid cases on arrival were subsequently found negative. Others were already on anticoagulants and could not be included as this would have affected the blood test results.

Of the 155 patients recruited, 120 came from ED.

All follow-up samples were carried out on the wards or in the intensive care unit, depending on where the patients had been moved to.

The samples were taken after 24 hours, three to five days and one week, which made it a seven-day operation for the team.

“We collected samples during the evenings and at weekends” said Jan. “Once you have recruited a patient you have to do the follow-up samples to make sure you’re getting them at the appropriate time.

“If that meant coming in on a Saturday or Sunday, that’s what we did, along with other members of the team.”

Jun said all the staff in ED, intensive care and the wards had been fully cooperative and supportive. That was vital as, without their support, it would have been impossible to complete the study.

“They were really accommodating. They wanted us to do the research because they were seeing first-hand the consequences of the disease and how it was affecting patients.

“It was a sharp learning curve for me and a fantastic experience. I learnt a lot about the methodology of carrying out research in acute illness.”

However, for Jan in particular, it was a very different experience to what she was used to.

“As a research assistant I’m more usually in an environment where I would be handling and analysing data,” she said.

“I have recruited patients before on other acute studies, but the Covid situation was a completely different environment.

“Initially you are a bit wary. You are very aware of the situation you’re walking into. But we have been particularly careful and strictly followed all recommended guidelines and protocols.

“I was given confidence by all the staff and had total admiration for their professionalism and the dedicated care they gave to these very sick patients.”

The study, which also involves the collection and recording of large volumes of clinical and scientific data at the bedside, is led by Professor Adrian Evans and his consultant colleague Dr Suresh Pillai.

Professor Evans, the research centre’s Director, said the volume of data to be analysed meant the results of the study would not be published until later in the year.

He added: “The patient recruitment target was met within four months of an eight-month grant period.

“This is a tribute to the entire team effort and Jan and Jun’s highly effective partnership.

“The reason we recruited so quickly was because of their professional and sensitive approach and the huge efforts of the whole team and all those involved in the health board such as laboratory medicine.”

Dr Pillai said: “It was particularly remarkable because of the intensity of the disease and the hazardous environment Jun and Jan had to work in.

“Undertaking research in acute settings is the most difficult because of the sensitivities involved for patients, relatives and staff.”

Leave a Reply

View Comments